The Corporal Passion Of Our Lord Jesus Christ

ONE of the most deeply-rooted legends in human minds is that of the hard-heartedness of surgeons: we are given to understand that enthusiasm blunts our sensitivity, and that this habitual attitude, reinforced by the necessity of causing pain in order to achieve good, makes us into serenely insensible beings. This is not the case. Even if we set ourselves firmly against emotion, which must never be shown, and, even within us, must never interfere with the surgical act (just as a boxer instinctively contracts his solar-plexus muscles when expecting a blow), nevertheless, pity always remains alive in us, and even becomes purer as one grows older. When for many years one has been bending over the sufferings of others, when one has even experienced them oneself, one is certainly nearer to compassion than to indifference, because one is better acquainted with pain, because one knows better what are its causes and its effects.

Besides, when a surgeon has meditated on the sufferings of the Passion, when he has worked out its timing and its physiological circumstances, when he has methodically set himself to reconstruct all the stages of that martyrdom of a night and a day, he can, more than the most eloquent preacher, more than the most saintly ascetics (apart from those to whom was granted a direct vision, and who were overwhelmed by it), as it were share in the sufferings of Christ. I can assure you of a dreadful thing, I have reached a point when I no longer dare to think of them. No doubt this is cowardice, but I hold that one must either have heroic virtue or else fail to understand; that one must either be a saint or else irresponsible, in order to do the Way of the Cross. I no longer can.

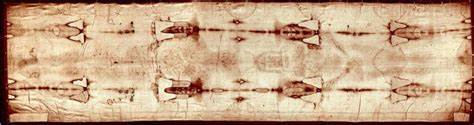

And yet it is about this Way of the Cross that I have been asked to write, and I would not refuse to do so, for I am sure it should do good. O bone et dulcissime Jesu, come to my aid. You, Who had to bear them, make me able to describe Your sufferings. Perhaps, by forcing myself to be objective, in opposing emotion with my surgical ” insensibility,” perhaps I shall be able to reach the goal. If I should shed tears before the end, do you, my good friendly reader, do the same as me and not be ashamed; it will simply be that you have understood. Please follow me in what I say: for our guides we have the sacred books and the Holy Shroud, the authenticity of which has been demonstrated to me by scientific research. 1

The Passion really begins at the Nativity, since Jesus, in His divine omniscience, always knew, saw and willed the sufferings which were awaiting His Humanity. The first blood shed for us was on the occasion of the Circumcision, eight days after Christmas. One can readily imagine what it must be for a man to be able exactly to foresee his martyrdom.

The holocaust was to begin, in fact, at Gethsemani. Jesus, having given to His own His body to eat and His blood to drink, leads them by night to that grove of olives where they were in the habit of going. He allows them to rest at the entrance, taking with Him a little further His three intimate friends, from whom He separates Himself about a stone’s throw, in order to prepare Himself in prayer. He knows that His hour is come. He has Himself sent on the traitor of Carioth: quod facis, fac citius.2 He is eager to be finished with it, and it is His will. But as He has assumed, by incarnating Himself, this form of a slave which is our humanity, the latter rebels, and there is all the tragedy of the struggle between His will and human nature. Coepit pavere et toedere. 3

This cup which He must drink contains two bitternesses: first, the sins of men which He must take on Himself, on Him the Just One, in order to ransom His brothers, and this was probably the worst: an ordeal that we cannot imagine, because it is the saints amongst us who feel most keenly their worthlessness and their baseness. We shall perhaps better understand His anticipation. The experience beforehand of the physical tortures, which He already suffers in thought; nevertheless, we have only experienced the retrospective shudder at those sufferings which are passed. It is inexpressible. Pater, si vis, transfer calicem istud a me: verumtamen non mea voluntas sed tua fiat4. It is His Humanity speak-ing … and which submits, for His Divinity knows what it wills from all eternity; the Man is caught in a blind alley. His three faithful friends are asleep, præ tristitia, as St. Luke says.5 Poor men!

The struggle is terrible; an angel comes to strengthen Him, but at the same time, so it seems, to receive His acceptance. Et factus in agonia, prolixius orabat. Et factus est sudor ejus sicut guttæ sanguinis decurrentis in terram.6 It is the sweat of blood which certain rationalist exegetists, scenting some miracle, have treated as symbolical. It is strange to note what nonsense these modern materialists can talk in regard to scientific matters. Let us remember that the only evangelist to record the fact was a physician. And our venerated colleague, Luke, medicus carissimus,7 does so with the precision and conciseness of a good clinician. Hematidrosa is a very rare phenomenon, but has been well described. It is produced, as Dr. Le Bec has written, in ” very special conditions: great physical debility accompanied by violent mental disturbance, following on profound emotion or great fear.”8 (Et cæpit pavere et tædere.) Dread and horror are here at their maximum, and so is mental disturbance. This is what St. Luke means by agonia, which in Greek signifies a combination of struggle and anxiety. “And His sweat became as drops of blood, trickling down upon the ground.”

How can one explain this? There is an intense vasolidation of the subcutaneous capillaries, which burst on contact with the millions of sudoripary glands. The blood mingles with the sweat, and it is this mixture which forms into beads and flows over the whole body, in a sufficient quantity to fall to the ground. Note that this microscopic haemorrhage is produced all over the skin, which thus already suffers a general injury, and becomes sore and tender while awaiting the blows to come. But we must move onwards.

Here are Judas and the temple attendants, armed with swords and staves; they have lanterns and ropes. As this criminal case must be judged by the procurator, they have with them a platoon of the Roman guard; the tribune of Antonia accompanies them, to make sure things are orderly. It is not yet the turn of the Romans; they are behind these fanatics, aloof and contemptuous. Jesus steps forward; one word from Him is enough to throw His assailants to the ground, the last manifestation of His power, before He abandons Himself to the divine will. Honest Peter seizes the opportunity to cut off the ear of Malchus and, His last miracle, Jesus has healed it.

But the yelling crowd have recovered, and have bound Christ; they lead Him away, without courtesy, one may well imagine, and the minor actors are allowed to get away. To all appearances He has been abandoned. Jesus knows that Peter and John are following Him a longe,9 and that Mark will only escape arrest by running away naked, leaving with the guard the cloth which had been wrapped round him.

Here they are before Caiphas and the Sanhedrin. It is by now the middle of the night, and it is clear that they are acting, according to previous instructions. Jesus refuses to answer: as for His doctrine, He has taught it publicly. Caiphas is all at sea, furious, and one of the soldiers, expressing his vexation, gives the accused a hard blow in the face: Sic respondes pontifici?10

Nothing has been achieved; they must wait for the morning, till the witnesses can give evidence. Jesus is dragged from the hall into the courtyard. He sees Peter, who has denied Him three times, and with one look He pardons him. He is dragged into some underground room, and the rabble of attendants is going to enjoy itself to the full at the expense of this false prophet, duly bound, Who, a short time ago, was able to throw them to the ground by who knows what sorcery. He is beset with slaps and blows; they spit on His face, and as there will be no chance of sleep, they are going to amuse themselves a little. A cloth is tied over His head, and each one is going to have his turn; their slaps ring out, and these brutes are heavy-handed: “Prophesy; tell us, O Christ, who struck You?” His body is already full of pain, His head is ringing like a bell; He has fits of giddiness … and He is silent. With one word He could destroy them, et non aperuit os suum.11 This rabble ends by growing weary, and Jesus waits.

In the early morning the second hearing takes place, and a wretched string of false witnesses files past, proving nothing. He must condemn Himself, by affirming His Divine Sonship, and this base second-rate actor Caiphas, proclaims the blasphemy by tearing his robes. Oh, you may be sure, the good, careful Jews, who are not given to wasting money, have a slit all ready and lightly sewn up, which can be used many times over. All that remains is to obtain from Rome the death sentence which she has reserved to herself in this protectorate country.

Jesus, already worn out with fatigue and bruised all over with blows, is now to be dragged to the other end of Jerusalem, to the upper town, to the tower of Antonia, a sort of citadel, from which the majesty of Rome keeps order in this city that is always too excited for her taste. The glory of Rome is represented by a miserable official, a little Roman of the knight class, a self-made man, who is only too ready to hold this difficult command over a fanatical, hostile and hypocritical people, Pilate’s great care is to keep his position, wedged between the imperious orders of Rome and the sly ways of these Jews, who are often very well in with the emperor. In short, he is a poor type of man. He has but one religion, if he has one at all, that of Divus Cæsar.12 He is the mediocre product of a barbarous civilisation, of a materialist culture. One should not be too hard on him for this, for he is that which it has made him; the life of a man has little value for him, especially if he does not happen to be a Roman citizen. He has been taught nothing about pity, and he knows but duty, to maintain order. (In Rome this is considered very suitable!) All these quarrelsome Jews, with their lies and their superstitions, with their taboos and their mania for washing for no reason, their servility and their insolence, and those cowardly denunciations to the Ministry of a colonial administration which is doing its best. The whole thing disgusts him. He despises them … and he fears them.

With Jesus it is just the opposite (although in what a state does He appear before him, covered with bruises and spittle); Jesus impresses him, and there is something he likes about Him. He will do everything he can to rescue Him from the claws of these fanatics: et quærebat dimittere illum. 13 Jesus is a Galilean; let us pass Him on to that old blackguard, Herod, who is always playing at being a king, and thinks he is somebody. But Jesus despises that old fox and refuses to answer him. And now He is back, accompanied by this yelling crowd and these insufferable Pharisees, for ever whining on a high-pitched note and wagging their heads. They are hateful creatures! Let them remain outside, especially as they would consider themselves defiled merely through entering a Roman pretorium.

Pontius questions this poor Man, in whom he is interested. And Jesus does not despise him. He pities him for his invincible ignorance; He answers him gently, and even tries to teach him. If there was no more than this howling rabble outside, a sortie by the guard cum gladio14 would quickly silence the more noisy and disperse the others. It is not so long that I massacred certain Galileans in the temple who were showing rather too much excitement. Yes, but these crafty Sanhedrin men are beginning to insinuate that I am no friend to Cæsar, and that is no laughing matter. And then, mehercle,15 what on earth is all this talk about the King of the Jews, the Son of God and the Messias? Had he read the Scriptures, Pilate might, perhaps, have been another Nicodemus, for Nicodemus also is a coward; but it is cowardice which is going to break down the dikes. This is a Just Man; I will have him scourged (oh, Roman logic!), and then these brutes will maybe have some pity.

But I also am a coward, for if I continue to delay, pleading for this wretched Roman, it is only to put off my own pain. Tunc ergo apprehendit Pilatus Jesum et flagellavit. 16

The soldiers of the guard then take Jesus into the hall of the pretorium, and all the men of the cohort are summoned to the scene; there are few amusements in this occupied country. And yet the Saviour has often shown Himself to have a special sympathy with soldiers. He admired the trust and humility of the centurion and his affectionate care for the servant whom He healed. Later, it will be the centurion of the guard on Calvary who will be the first to proclaim His divinity. The cohort seems, however, to be seized by a collective frenzy which Pilate had not foreseen. Satan is there, breathing hatred into them.

But that is enough. Nothing is said, there are just blows; and let us try to follow to the end. They remove His clothes and bind Him, naked, to a column of the hall. The arms are held up in the air and the wrists are bound to the shaft.

The scourging is done with numerous thongs to which are fixed, at some distance from the loose ends, two balls of lead or small piece of bone. (Certainly, the stigmata on the Holy Shroud correspond to this type of flagrum.) The number of strokes is limited to thirty-nine by Hebrew law. But His executioners are legionaries without restraint, and they will go on to the point of making Him faint. There are, in fact, marks without number on the shroud, and they are nearly all on the back; the front of the body is against the column. They are to be seen on the back, on the shoulders and the loins. The lashes fall on His thighs and on the calves of His legs; and it is there that the ends of the thongs, beyond the balls of lead, encircle the limb and mark it with a furrow right round to the other side.

There are two executioners one on each side of Him, of unequal height (all this may be deduced from the direction of the marks on the shroud). They alternate their strokes, with great zest. At first, the strokes leave long livid marks, long blue bruises beneath the skin. Remember that the skin has already been affected; that it is sore owing to the millions of little intra-dermic haemorrhages brought about by the sweat of blood. Further marks are made by the balls of lead. Then the skin, into which the blood has crept, becomes tender and breaks under fresh blows. The blood pours out; shreds of skin become detached and hang down. The whole of the back is now no more than a red surface, on which great furrows stand out like marble; and, here and there, everywhere, there are deeper wounds caused by the balls of lead. These wounds, shaped like a halter (the two balls and the thong between them), will make their marks on the shroud.

At each stroke, the body gives a painful shudder. But He has not opened His mouth, and His silence redoubles the Satanic rage of His executioners. It is no longer a cold-blooded, judicial execution; it is the unchaining of demons. The blood flows from His shoulders down to the earth (the large paving-stones are covered with it), and is scattered like rain by the lifted whips as far as the red cloaks of the onlookers. But the strength of the Victim soon begins to fail; sweat breaks out on His forehead; His head whirls with giddiness and nausea; shivers run down His spine; His legs give way under Him, and if He was not tied up by His wrists, He would slip down into the pool of blood. They have completed the count, even though they have not counted. After all, they have not received the order that He should die under the lash. Let Him recover a bit; there will be further chances for amusement.

And this great Fool claims to be a king, as if He held it under the Roman eagles, and what is more, to be King of the Jews; of all ridiculous things! He has had some trouble with His subjects; what matter, we will be His faithful supporters. Quick, a robe, a sceptre. He has been put to sit at the base of the column (not a very secure place for His Majesty!). An old legionary’s cloak thrown over His naked shoulders confers on Him the royal purple; a reed in His right hand, and everything is complete, except for the crown; now for something original! (For nineteen centuries He will be known by this crown, which no other crucified being has worn). In the corner there is a bundle of faggots, cut from those little trees which thrive on the outskirts of the city. The wood is flexible and covered with long thorns, much longer and sharper and harder than those of the acacia. They plait with caution (ugh! it hurts!) something like the bottom of a basket, which they place on His head. They beat down the edges and with a band of twisted rushes they bind it on the head from the nape of the neck to the forehead.

The thorns dig into the scalp and it bleeds. (We surgeons know how much a scalp can bleed.) The top of the head is already clotted with blood; long streams of blood have flown down to the forehead, under the band of rushes, have soaked into the tangled hair and into the beard The comedy of adoration has begun. Each in turn comes forward and bows the knee before Him, with a horrible grimace, followed by a great blow: “Hail, King of the Jews!” But He answers nothing. His poor face, so ravaged and pale, displays no movement. It really is not funny! In their exasperation His faithful subjects spit in His face. “You don’t know how to hold the sceptre, give it here!” There, a blow on the crown of thorns, which makes it sink further in, and then fresh blows. I cannot remember, did He receive it from one of the legionaries, or from the gentlemen of the Sanhedrin? But I can see that a blow from a stick delivered from the side has made a horrible bruise on His face, and that His fine well-shaped nose has been disfigured owing to the septum being broken. The blood is flowing from His nostrils. Oh, my God, this is enough!

But now Pilate is back, rather worried about the prisoner-what have these brutes been doing to Him? Well, they have dealt with Him all right. If the Jews are not satisfied now!-He will show Him to them from the balcony of the pretorium, in His royal robes, and is quite astonished at the pity he finds himself feeling for this poor bedraggled creature. But he has underestimated their hatred. Tolle, crucifige! 17 What fiends they are! And then they put forward the argument that terrifies him: “If thou release this man, thou art not Cæsar’s friend. For whosoever maketh himself a king speaketh against Cæsar.”18 The coward then surrenders completely and washes his hands. As St. Augustine would write later, however, “It is not thou, O Pilate, who didst kill him, but the Jews, with their cutting tongues; and when compared with them, thou art far more innocent.”

They tear the cloak from Him, which has already stuck to His wounds. The blood starts to flow once more; He gives a great shudder. They replace His own clothes, which become stained with red. The cross is ready, they place it on His shoulders. By what miracle of strength does He remain standing beneath this burden? It is not in fact, the whole cross, but only the great horizontal beam, the patibulum, which He must carry as far as Golgotha, but still it weighs nearly 125 pounds. The vertical stake, the stipes, is already planted on Calvary.

And so He starts on His journey, with bare feet, along the rough roads strewn with stones. The soldiers pull the cords which bind Him, anxious to know whether He will last out till the end. Two thieves follow Him with the same equipment. The road is fortunately not very long, about 650 yards, and the hill of Calvary is just outside the gate of Ephraim. But the journey is a very chequered one, even inside the ramparts. Jesus painfully puts one foot before the other, and He often falls. He falls on to His knees which are soon all raw. The soldiers who form the escort lift Him up, and are not too brutal about it, for they feel He might easily die on the way.

And all the time there is that beam, balanced on His shoulders, bruising Him, and which seems to wish to force its way into His back. I know what it is like: in the time gone by, when serving with the 5e Genie, 19 I have carried railway sleepers on my back; they were well planed, and yet I can still remember how they seemed to force their way right into one’s shoulders, even into my shoulders which were in excellent condition. But His shoulders are covered with raw places, which open up again and get larger and deeper with each step He takes. He is worn out. On His seamless coat there is a large patch of blood which gets ever larger till it reaches right down His back. He falls again and this time at full length; the beam falls off Him; will He be able to get up again? Luckily at this moment a man passes by, on his way back from the fields, one Simon of Cyrene, who is soon, along with his sons Alexander and Rufus, going to be a good Christian. The soldiers make him carry this beam, and the good fellow is willing enough; oh, how well I would do it! There is at last only the slope of Golgotha to be climbed, and they make their painful way to the top of the hill. Jesus sinks to the ground and the crucifixion begins.

Oh, it is not very complicated; the executioners know their work. First of all He must be stripped. The lower garments are dealt with easily enough, but the coat has firmly stuck to His wounds, that is to say, to His whole body, and this stripping is a horrible business. Have you ever removed the first dressing which has been on a large bruised wound, and has dried on it? Or have you yourself ever been through this ordeal, which sometimes requires a general anaesthetic? If so, you know what it is like. Each thread has stuck to the raw surface, and when it is removed it tears away one of the innumerable nervous ends which have been laid bare by the wound. These thousands of painful shocks add up and multiply, each one increasing the sensitivity of the nervous system. Now, it is not just a question of a local lesion, but of almost the whole surface of the body, and especially of that dreadful back. The executioners are in a hurry and set about their work roughly. Perhaps it is better thus, but how does this sharp, dreadful pain not bring on a fainting fit? How clear it is that from beginning to end He dominates, He directs His Passion.

The blood streams down yet again. They lay Him down on His back. Have they left Him the narrow loin-cloth which the modesty of the Jews has been able to preserve for those condemned to this death? I must own that I do not know: it is of little importance; in any case, in His shroud, He will be naked. The wounds on His back, on His thighs and on the calves of His legs become caked with dust and with tiny pieces of gravel. He has been placed at the foot of the stipes, with His shoulders lying on the patibulum. The executioners take the measurements. A stroke with an auger, to prepare the holes for the nails, and the horrible deed begins.

An assistant holds out one of the arms, with the palm uppermost. The executioner takes hold of the nail (a long nail, pointed and square, which near its large head is 1/3 of an inch thick), he gives Him a prick on the wrist, in that forward fold which he knows by experience. One single blow with the great hammer, and the nail is already fixed in the wood, in which a few vigorous taps fix it firmly.

Jesus has not cried out, but His face has contracted in a way terrible to see. But above all I saw at the same moment that His thumb, with a violent gesture, is striking against the palm of His hand: His median nerve has been touched. I realise what He had been through: an inexpressible pain darts like lightning through his fingers and then like a trail of fire right up His shoulder, and bursts in His brain. The most unbearable pain that a man can experience is that caused by wounding the great nervous centres. It nearly always causes a fainting fit, and it is fortunate that it does. Jesus has not willed that He should lose consciousness. Now, it is not as if the nerve were cut right across. But no, I know how it is, it is only partially destroyed; the raw place on the nervous centre remains in contact with the nail; and later on, when the body sags, it will be stretched against this like a violin-string against the bridge, and it will vibrate with each shaking or movement, reviving the horrible pain-This goes on for three hours.

The other arm is pulled by the assistant, the same actions are repeated and the same pains. But this time, remember, He knows what to expect. He is now fixed on the patibulum, to which His shoulders and two arms now conform exactly. He already has the form of a cross: how great He is!

Now, they must get Him on His feet. The executioner and his assistant take hold of the ends of the beam and then hold up the condemned man Who is first sitting, then standing, and then, moving Him backwards, they place Him with His back against the stake. But this is done by constantly pulling against those two nailed hands, and one thinks of those median nerves. With a great effort, and with arms extended (though the stipes is not very high), quickly, for it is very heavy, and with a skilful gesture, they fix the patibulum on the top of the stipes. On the top with two nails they fix the title in three languages.

The body, dragging on the two arms, which are stretched out obliquely, is sagging a bit. The shoulders, wounded by the whips and by carrying the cross, have been painfully scraped against the rough wood. The nape of the neck, which was just above the patibulum, has been banged against it during the move upwards, and is now just above the stake. The sharp points of the great cap of thorns have made even deeper wounds in the scalp. His poor head is leaning forward, for the thickness of His crown prevents Him leaning against the wood, and each time that He straightens it He feels the pricks.

The body is meanwhile only held by the nails fixed into the two wrists -Once more those median nerves ! He could be held fast with nothing else. The body is not slipping forwards, but the rule is that the feet should be fixed. There is no need of a bracket for this; they bend the knees and stretch the feet out flat on the wood of the stipes. Why then, since it is useless, is the carpenter given this work to do? It is certainly not in order to lessen the pain of the crucified. The left foot is flat against the cross. With one blow of the hammer, the nail is driven into the middle of it (between the second and third metatarsal bones). The assistant then bends the other knee, and the executioner, bringing the left foot round in front of the right which the assistant is holding flat, pierces this foot with a second blow in the same place. This is easy enough, and with a few vigorous blows with the hammer the nail is well embedded in the wood. This time, thank God, it is a more ordinary pain, but the agony has scarcely begun. The whole work has not taken the two men much more than two minutes and the wounds have not bled much. They then deal with the two thieves, and the three gibbets are arranged facing the city which kills its God.

Do not let us listen to these triumphant Jews, as they insult Him in His pain. He has already forgiven them, for they know not what they do. Jesus has at first been in a state bordering on collapse. After so many tortures, for a worn-out body this immobility is almost a rest, coinciding as it does with a general lowering of His vitality. But He thirsts. He has not said so as yet. Before lying down on the beam, He has refused the analgesic drink, of wine mingled with myrrh and gall, which is prepared by the charitable women of Jerusalem. He wishes to know His suffering in its completeness; He knows that He will conquer it. He thirsts. Yes, Adhæsit lingua me faucibus meis.20 He has neither eaten nor drunk anything since the evening before, and it is now midday. His sweat in Gethsemani, all His fatigues, His loss of blood in the pretorium and at other times, and even the small amount now flowing from His wounds, all this has taken a good part of His sum-total of blood. He thirsts. His features are drawn, His pale face is streaked with blood which is congealing everywhere. His mouth is half open and His lower lip has already begun to droop. A little saliva has flowed down to His beard, mingled with the blood from His injured nose. His throat is dry and on fire, but He can no longer swallow. He thirsts. How can one recognise the fairest of the children of men in this swollen face, all bleeding and deformed? Vermis sum et non homo.21 It would be horrible, if one did not see shining through it the serene majesty of God Who wishes to save His brothers. He thirsts. And He will soon say it, so as to fulfil the Scriptures. A great simpleton of a soldier, wishing to hide his compassion beneath a mocking jest, soaks a sponge in his acid posca, acetum as the Gospels call it, and holds it up to Him at the end of a reed. Will He drink only a drop of it? It is said that the fact of drinking brings on a mortal fainting fit in these poor, condemned creatures. How then, after the sponge had been held up to Him, was He able to speak two or three times? No, He will die at His own hour. He thirsts.

And that has just begun. But, a moment later, a strange phenomenon occurs. The muscles of His arms stiffen of themselves, in a contraction which becomes more and more accentuated; His deltoid muscles and His biceps become strained and stand out, His fingers are drawn sharply inwards. It is cramp! You have all had some experience of this acute, progressive pain, in the calves of the legs, between the ribs, a little everywhere. One must immediately relax the contacted muscle by extending it. But watch-on His thighs and on His legs there are monstrous rigid bulges, and His toes are bent. It is like a wounded man suffering from tetanus, a prey to those horrible spasms, which once seen can never be forgotten. It is what we describe as tetanisation, when the cramps become generalised, which is now happening. The stomach muscles become tightened in set undulations, then the intercostal, then the muscles of the neck, then the respiratory. His breathing has gradually become shorter and lighter. His sides, which have already been drawn upwards by the traction of the arms, are now exaggeratedly so; the solar plexus sinks inwards, and so do the hollows under the collar-bone. The air enters with a whistling sound, but scarcely comes out any longer. He is breathing in the upper regions only, He breathes in a little, but cannot breathe out. He thirsts for air. (It is like someone in the throes of asthma.) A flush has gradually spread over His pale face; it has turned a violet purple and then blue. He is asphyxiating. His lungs which are loaded with air can no longer empty themselves. His forehead is covered with sweat, His eyes are prominent and rolling. What an appalling pain must be hammering in His head! He is going to die. Well, it is best so. Has He not suffered enough?

But no, His hour has not yet come. Neither thirst, nor hæmorrhage, nor asphyxia, nor pain will be able to overcome the Saviour God, and if He dies with these symptoms, He will only die in truth because He freely wills it, habens in potestate ponere animam suam et recipere eam. 22 And thus it is that He will rise again.

What, then, is happening? Slowly, with a superhuman effort, He is using the nail through His feet as a fulcrum, that is to say He is pressing on His wounds. The ankles and the knees stretch themselves out bit by bit, and the body is gradually lifted, thus relieving the pressure on the arms (a pressure which was of very nearly 240 pounds on each hand). We thus see how, through His own efforts, the phenomenon grows less, the tetanisation recedes, the muscles become relaxed, anyway those of the chest. The breathing becomes more ample and moves down to a lower level, the lungs are unloaded and the face soon resumes its former pallor.

Why is He making all this effort? It is in order to speak to us: Pater, dimitte illis. 23 Yes, may He indeed forgive us, we who are His executioners. But a moment later His body begins to sink down once more … and the tetanisation will come on again. And each time that He speaks (we have anyway preserved seven of His words), and each time that He wishes to breathe, it will be necessary for Him to straighten Himself, to get back His breath, holding Himself upright on the nail through His feet. And each movement has its echo, so to speak, in His hands, in inexpressible pain (those median nerves once again!). It is a question of periodical asphyxiation of the poor unfortunate Who is being strangled and then allowed to come back to life, to be choked once more several times over. He can only escape from this asphyxiation for a moment at a time and at the cost of terrible suffering, and by an effort of the will. And this is going to last three hours. O my God, may You be able to die!

I am there at the foot of the cross, with His Mother and John and the women who attended upon Him. The centurion, who had been standing a little apart, is observing the scene with an attention that has already become respectful. Between two attacks of asphyxiation, He draws Himself up and speaks: “Son, behold Thy Mother.” Oh, yes, dear Mother, you who adopted us from that day!-a little later that poor wretch of a thief manages to have the gate of paradise opened for him. But when, O Lord, are You at last going to die?

I know well that Easter awaits You, and that Your body will not decay as ours do. It is written: Non dabis sanctum tuum videre corruptionem.24 But, O poor Jesus (forgive a surgeon for these words), all Your wounds are becoming infected; this was certain to happen. I can see clearly how a light-coloured transparent lymph is oozing from them, which collects at the deepest part in a wax-like crust. On the earliest wounds false membranes are forming, which secrete a serum mixed with pus. It is also written: Putruerunt et corrupta sent cicatrices meæ. 25

A swarm of horrible flies, of great yellow and blue flies such as one finds in abattoirs and charnel-houses, is whirling the whole time round His body, and they swoop down on the different wounds in order to suck at them and to lay their eggs. They set on His face and cannot be driven away. Fortunately, the sky has during the last moments gone dark, and the sun is hidden; it has suddenly become very cold, and these daughters of Beelzebub have one by one taken their departure.

It will soon be three o’clock. At last! Jesus is holding out the whole time. Every now and then He draws Himself up. All His pains! His thirst, His cramps, the asphyxiation and the vibration of the two median nerves have not drawn one complaint from Him. But, while His friends are there indeed, His Father, and this is the last ordeal, His Father seems to have forsaken Him. Eli, Eli, lamma sabacthani? 26

He now knows that He is going. He cries out consummatum est.27 The cup is drained, the work is complete. Then, drawing Himself up once more and as if to make us understand that He is dying of His own free will, iterum clamans voce magna:28 “Father, into Thy hands I commend My Spirit” (habens in potestate ponere animan suam).29 He died when He willed to do so. I wish to hear of no more physiological theories!

Laudato si Missignore per sora nostra morte corporale!30 O yes, Lord, may You be blessed, for having truly willed to die. For there was nothing we could do. With a last sigh Your head dropped slowly towards me, with Your chin above the breastbone. I can see Your face straight before me, it is now relaxed and calm, and in spite of its dreadful stigmata, it is illuminated by the gentle majesty of God, Who is always present there. I have thrown myself on my knees before You, kissing Your pierced feet, from which the blood is still flowing, though it is coagulating at the tips. The rigor mortis has seized You in brutal fashion, like a stag run down in the chase. Your legs are as hard as steel … and burning. What unheard-of temperature has given You this tetanic spasm?

There has been an earthquake; what is that to me? And the sun has undergone an eclipse. Joseph has gone to ask Pilate for Your body, and he will not be refused. The latter hates the Jews, who have forced him to kill You; that writing above Your head proclaims his rancour for all to see; “Jesus, King of the Jews,” has been crucified like a slave! The centurion has gone to make his report, and the brave man has proclaimed You to be truly the Son of God. We are going to lower You, and it will be easy, once the nail has been taken out of the feet. Joseph and Nicodemus will unfasten the beam of the stipes. John, Your beloved disciple, will bear Your feet; with two others we will support Your loins, using a sheet twisted to make a rope. The shroud is ready, on this stone nearby, in front of the sepulchre; and there, taking their time, they will remove the nails from Your hands. But who is this?

Oh, yes, the Jews must have asked Pilate to clear the hill of these gibbets which offend the eye and would defile to-morrow’s feast. A brood of vipers, who strain at a gnat and swallow a camel! Some soldiers break the legs of the thieves, giving them great blows with an iron bar. They now hang miserably, and as they can no longer raise themselves on the ropes binding their legs, tetanisation and asphyxiation will soon have finished them.

But this does not apply to You. Os non comminuetis ex eo.31 Can you not leave us in peace? Cannot you see He is dead?-No doubt, they say. But what is this idea that one of them has? With an exact and tragic gesture he has raised the shaft of the lance and with one blow upwards on the right side, he drives it in deep. But why? “And immediately there came out blood and water.”32 John truly saw it, and I also, and we would not lie: a broad stream of dark liquid blood, which gushed out on to the soldier, and slowly flowed in dribbles over the chest, coagulating in successive layers. But at the same time, and specially noticeable at the edges, there flows a clear liquid like water. Let us see, the wound is below and to the outside of the nipple (the fifth space), and the blow from below. It is therefore the blood from the right auricle, and the water issued from the pericardium. But then, O poor Jesus, Your heart was compressed by this liquid, and apart from everything else You had the agonising cruel pain of Your heart being held as in a vice.

Had we not already seen enough? Was it so that we should know this, that this man performed this odd aggressive act? The Jews might also have made out that You were not dead but had fainted; Your resurrection needed this testimony. Thank you, soldier, thank you, Longinus; one day you will die as a Christian martyr.

And now, reader, let us thank God Who has given me the strength to write this to the end, though not without tears! All these horrible pains that we have lived in Him, were foreseen by Him all through His life; He premeditated them and willed them, out of His love, so that He might redeem us from our sins. Oblatus est quia ipse voluit.33 He directed the whole of His passion, without avoiding one torture, accepting the physiological consequences, without being dominated by them. He died when and how and because He willed it.

Jesus is in agony till the end of time. It is right, it is good to suffer with Him and to thank Him, when He sends us pain, to associate ourselves with His. We have, as St. Paul writes, to complete what is lacking in the passion of Christ, and with Mary, His Mother and our Mother, to accept our fellow-suffering fraternally and with joy.

O Jesus, You Who had no pity on Yourself, You Who are God, have pity on me who am a sinner.FOOTNOTES

- Cf. The Five Wounds of Christ, by Dr. Pierre Barbet, translated by M. Apraxine. (Clonmore & Reynolds.)

- “That which thou dost, do quickly.” (Jn. XIII, 27.)

- “He began to fear and to be heavy.” (Mk. XIV, 33.)

- ” Father, if thou wilt, remove this chalice from me: but yet not my will but thine be done.” (Lk. XXII, 42.)

- “For sorrow.” (Lk. XXII, 45.)

- “And being in an agony, he prayed the longer. And his sweat became as drops of blood, trickling down upon the ground.” (Lk. XXII, 43, 44.)

- “The beloved physician.”-St. Paul’s Epistle to the Colossians

- Dr. Le Bec, Le Supplice de la Croix (The Torture of the Cross); a physiological study of the Passion, published some time ago, in which my former colleague at Saint-Joseph shewed astonishing foreknowledge. My experience has confirmed and more clearly defined most of his views. As for any fresh contributions of my own, he has received them enthusiastically, which I greatly value.

- “Afar off.” Mk. XIV, 54; Jn. XVIII, 15.

- “Answerest thou the High Priest so?” Jn. XVIII, 22.

- “And he opened not his mouth.” Isa. LIII, 7.

- “The Divine. Emperor.”

- “Pilate sought to release him.” Jn XIX, 12..

- Sword in hand.

- By Hercules

- “Then therefore Pilate took Jesus and scourged him.” Jn. XIX, 1.

- “Away with him, crucify him.” Jn. XIX, 15.

- Jn. XIX, I2

- 5th Regiment of Engineers

- “My tongue hath cleaved to my jaws.” Ps. XXI, 16.

- “I am a worm and no man.” Ps. XXI, 7

- “Having the power to lay down his life and to take it up again.”-St. Augustine, Treatise on the Psalms. (Ps. LXIII, ad vers., 3.)

- “Father, forgive them.” (Lk. XXIII, 34.)

- “Thou wilt not give thy holy one to see corruption.”-Ps. XV, 10.

- “My sores are putrefied and corrupted.” Ps. XXXVII, 6

- “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” Mt. XXVII, 46; Mk. XVI, 34; Ps. XXI, 1

- “It is consummated.” Jn. XIX, 30

- “Again crying with a loud voice.” Mt. XXVII, 50

- Lk. XXIII, 46.

- “May you be blessed, O Lord, for our sister the death of the body.” Canticle of the Creatures, St. Francis of Assisi.

- “You shall not break a bone of him.” Jn. XIX, 36; Ex. XII, 46.

- Jn. XIX, 34.

- “He was offered because it was his own will.” Is. LIII, 7